I've not posted anything for a while as I've been a little poorly. (Cough, cough, kersplot.) Illness came at a particularly bad time as I was supposed to be finishing

The Shakespeare Delusion (as well as sorting out all the publicity for the tryout in Suffolk) at the time and now have had to postpone. I hate postpone, it's a mean word, and I do normally try to keep the show on the road, but it had been a pretty horrendous Easter and I refuse to perform a not-quite-ready show to a not-very-big audience for the sake of being stubborn. So scratch 18th May from your minds - it's gone back to October, date tba. I have been indulging from my sickbed in a lot of Shakespeare for research purposes and I'm fascinated by how the silliest of notions can be given credence and respect. A rant on anti-Stratfordians will come in a further blog - for the moment I will only rant on the subject of the BBC "documentary"

Shakespeare in Italy for which commissioner, programme makers and researchers should get sacked. Whilst a well researched, expert led documentary series on Shakespeare and King James,

The Playwright and the King, languishes on BBC Four (where no one will watch it), a stupid, badly researched and, frankly, idiot led holiday programme pretending to be a documentary is placed on prime time BBC 2. It made claims without evidence, paraded partisan nobodies as experts and ignored decades of scholarship in favour of generalisations which are just plain wrong. As I emailed a friend of mine who teaches Shakespeare - one day your students will tell you that some of this nonsense is true. My anger is oddly palpable.

Bestilling my heaving breast and putting aside

The Shakespeare Delusion for a month or two, I'm now focused entirely on my production of

The Passion, which I've edited from the medieval mystery plays and which I'm directing for July - it's going to be epic, in all senses of the word, and I'm really excited about it. For the next two months expect posts mostly about that.

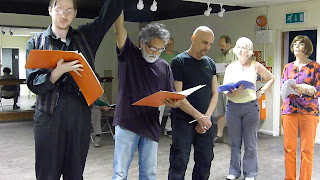

But back to my illness - the monkeys of fate were riding my back all through the hacking, sweating and wobbliness as, despite my malady, I still had to attend most rehearsals of

The Admirable Crichton which I was directing at the time. You know you must be doing something right as a director when the cast send you, not a get well soon card but a get well NOW card. I was touched. Now that both play and vomiting are past I thought I'd have a little look at the play itself for the bulk of this post. It is a curious little beast. As previously, I won't precis the play for you, if you don't know it go to wikipedia for a breakdown or read the text - it's available on Project Gutenberg for nothing.

The Admirable Crichton is a play that naturally calls to me across the desert wastes of discarded plays that time has strewn across the path of a directors interest. We share a name, albeit spelt differently, and the phrase is often, erroneously, used to describe myself (there is little to admire in my life). When Mr Barrie wrote the play he made famous a not unknown phrase which had previously been used to describe, even more erroneously, a real Crichton from the sixteenth century, who was a bit of a wild card, dying as he did in a duel with six people - a subject I've long thought of writing a play about.

The play

The Admirable Crichton is divorced entirely from its ancestor - it is light, frothy, fun and should be played with bold strokes. At first glance, especially in terms of plot and structure, it looks like a play that Bernard Shaw might have written; it has hints of social comedy, satire, a sense of overturning accepted values. Look again and Shaw would be appalled (though probably entertained) - he would have produced a play with a sharper, less forgiving eye and without the implicit acceptance of the status quo. Ultimately Barrie says that class structures are inevitable, that society will only be reformed into variations on a theme - Shaw would never have allowed that idea to pass. I haven't had a look to see if Shaw reviewed the original production, it would be interesting to see what he thought.

This isn't to say

Crichton isn't entirely toothless, it has a lot going for it in terms of attack on hypocrisy and occasional hints at downright naughtiness (some of the dialogue appears, from our modern eyes, to border on double entendre and it is very difficult to decide if it's deliberate or not), but for the most part the play is played with a straight bat.

It is, despite the plot being about class and social distinction, a nice little comedy. It doesn't aim for many big laughs, just an air of titters and general contentment from the audience. That maybe considered complacent for a work of theatre these days, but it is generally what the audience of the time and, for much of the country, what the audience of today actually wants; gentle escapement, a few laughs, nothing to frighten the horses.

It is, therefore, perfect, tonally speaking, for an amateur company in a village hall in a rural setting. That isn't to say it is an easy play to stage physically. It's a four act play that careers from a house in Mayfair to an island and back again with alarming speed. Both these major scene changes occur mid-way in each half, so you have to find ways a. of keeping the change short and b. do something to keep the audience happy while it occurs. Originally these scene changes would probably have been genuine intervals, so Barrie can't be blamed for being unrealistic in his stage craft. The play also asks for props and costumes in large quantities and requires a VAST chorus of servants who appear only in Act One - I believe Samuel French lists 17 parts - so not, on the surface at least, an easy proposition.

But the play does throw the producer a bone. Whilst all of these places, props and costumes are needed to some degree, many of them are only ever referenced by the text - in the way Shakespeare and his contemporaries would speak out a scene setting rather than building it, Barrie will refer to the amenities of the island in dialogue without requiring them physically to be used.

This isn't always true, of course. There are detailed stage directions throughout the play, discussing bits of business and acts that require props galore - but much of this we have reinvented as we went along. The problem with Barrie is his editorship of the text - he produced a script rich in detail, but with little clear marking as to how to carry out his plans. For example: he rarely gives a clear, straightforward indication of entrances and exits. Often it is assumed, hinted at in a block of prose, or not mentioned at all. And the vast amount of descriptive prose in the text makes it a task and a half for the cast to actually find their dialogue on the page. Finally, and most annoyingly for the director, he doesn't even include a cast list - which meant I had to spend an hour going through the play figuring out who was in the play (which when you haven't even decided whether you want to stage the play yet is quite a punt). Later editions may have corrected some of this issues - my copy definitely did not.

The tone of the play has been my over arching issue in rehearsal - the play appears relatively naturalistic at first glance, but after a couple rehearsals we all realised this was not the case. It is a stylised piece, people play up to situations, performing all the time in a hyper real way. I think the best way to describe it is... well, it feels more Broadway than West End. To be mean - subtlety would be wasted. That isn't to say there isn't detail to the performance, but the more I looked, the less there seemed to be inside any of the characters - just a series of surfaces reacting to their situation for comic effect.

The script also has a few dangling threads to it. Rather than a tightly weaved blanket of brilliance, there are occasional passages that are a bit loose, there's a thread missing that would tie all the action together. They are very minor issues that, were I to stage the play again, I would deal with by making a few minor re-writes. Keyhole surgery only, but I don't think I would let some of the dialogue to pass muster without correction - sentences that come out of nowhere, thoughts that don't quite come across, solved with an extra word or two, a half sentence here or there to darn up the gaps.

There are a few more serious challenges - the issue of the character Tweeny, who is left at the end of the play without any kind of resolution. The film version of the play (re-written from top to bottom, but faithful to the shape of the play) felt this absence and added clarity, but being a film it was essentially a sentimental version of the play and it's conclusion is similarly unsatisfactory. Taking up the mantle of Shaw again, it's a play that could do with a sharper ending, and he would not have left Tweeny's fate unexplored - but I fear we're drifting into the territory of Pygmalion, so I will stop making these unfair comparisons.

The level of the play is not that of Shaw - it is not trying to score points or really make people think. It isn't trying to say much, the shipwreck is a setup for a series of status changes - satire as a false front for a straightforward comedy of manners. The play that Barrie wrote doesn't need to tie up all the loose ends because in it Tweeny doesn't really matter - even Crichton's departure from the household is fairly perfunctory, a mechanical plot necessity. Sorting out what happens to Lady Mary is the primary function of Act Four, getting her across the obstacle course of her future mother in law and her (and her fiancees) indiscretions drives the comedy of the act. So long as everyone gets married or moved on, then the play can end.

Lady Mary is the core of the play - whilst Crichton, title character, is more the catalyst of the action. It is the reaction of Mary and the rest of the company to his changes that drives the comedy. They all react with large, sudden changes of emotion; from haughty aristocracy to sobbing simpletons at the toss of a line. Lady Mary, as the fawning love interest on the island, displays the greatest shift of character in relation to her status. She goes from being distant and disdainful to a girl who'll do anything for her man and, with some temperance, back again across the play - but this isn't a love story. The film thought it was, but the play always plays her love for Crichton as something deeply silly and comic - something fairly surface and reversible.

After leaving the island and returning to England she is all pragmatism - love for Crichton has gone, only respect is left. The last impulses from the island life, to tell her fiancee the truth about her life there, are soon dashed when he confesses his own affair - one that was actually consummated (possibly the closest the play gets to controversy) - and she agrees to forgive him and keep quiet herself. Lady Mary has learnt to play the game; she can see through the hypocrisy of her own life, but she will not make an effort to change it. She will keep up appearances and marry and be dutiful to a husband she doesn't love, who is obviously unreliable and only of value for his money - the only difference between her proposed marriage before the island and after is that now she knows it will be a sham.

Similarly, her father Lord Loam has learnt by the end of the play that his views on equality were not based on his own views. He was a blue blooded Tory who thought he was a socialist - it took the island to teach him to drop his own pretence. Again, whilst he has learnt, he hasn't actually changed. In fact, no one in the plat has deeply changed.

It is that lack of change that leaves

Crichton in the nice and harmless category of plays. Funny, fun and nice - but there is no bite, little depth and not even much length (it's a surprisingly short play) to raise this entertainment to a higher level of art or artistry.

As with my earlier post on

A Woman of No Importance I've damned the play with faint praise - it has to be said that in performance the audience laughed, the house was full and the general feeling was that of contentment. The play works and can be done very well - and is well known enough to draw an audience on its name alone (which always saves time, effort and money) - not many plays tick all those boxes.